Most data engineers trust their SQL. If the joins are correct and the filters are precise, the output should reflect the question being asked. Yet in many modern use cases, even a perfectly written query does not fully solve the problem because the underlying retrieval logic is limited to exact matches and structured conditions.

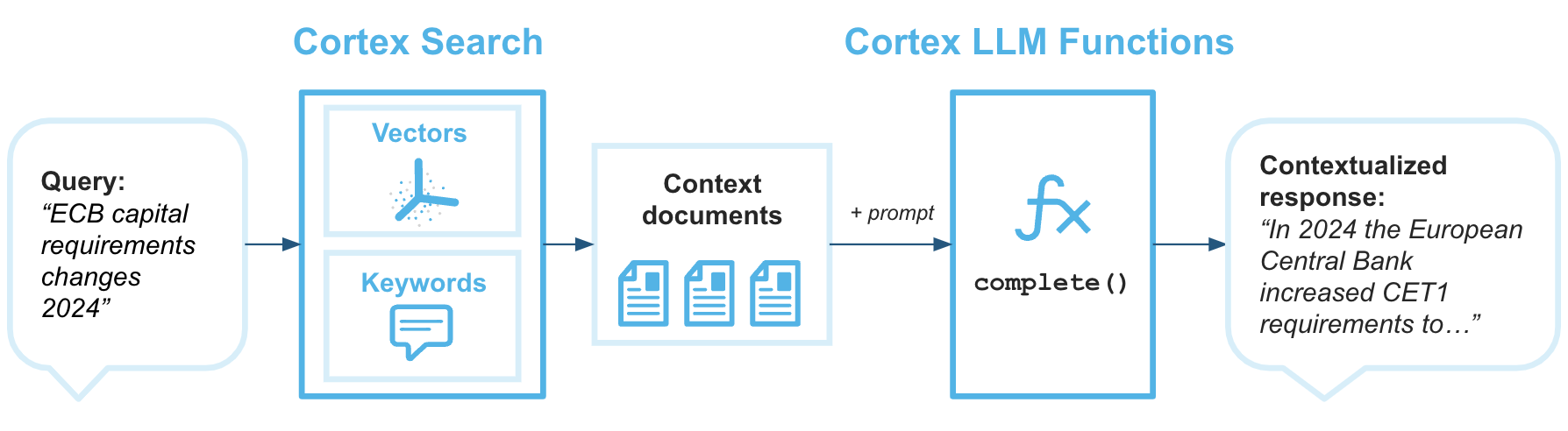

Consider an internal search system where users phrase questions differently each time, or a retrieval augmented generation workflow where an LLM needs contextually relevant chunks of documentation. In these cases, searching for keywords is rarely enough. Two sentences can carry the same meaning while sharing very few common terms, and traditional SQL predicates have no mechanism to recognize that relationship.

This gap between structured filtering and meaning-based retrieval is what semantic search addresses. Instead of evaluating equality or pattern matches, semantic search relies on vector representations of data and similarity calculations to surface results that are contextually aligned with the user’s intent.

With Snowflake introducing native support for vector data types and similarity functions, data engineers can now implement semantic retrieval directly inside the data platform. You are no longer forced to push embeddings into a separate vector database unless you have scale or performance constraints that justify it. You can design pipelines, store embeddings, and execute similarity search within Snowflake’s governed environment.

The important question, then, is not whether semantic search is useful. It is how Snowflake implements it under the hood and how you, as a data engineer, should model, store, and query vector data for production-grade systems.

Understanding Embeddings and Vector Storage in Snowflake

Before designing a semantic search system, it helps to clearly understand what is being stored and how Snowflake handles it.

An embedding is a numerical representation of text generated by a machine learning model. When a sentence is passed into an embedding model, the output is an ordered array of floating-point numbers. Each number represents one dimension in a high-dimensional vector space. Common embedding sizes include 768, 1024, or 1536 dimensions, depending on the model.

The individual numbers themselves are not meaningful to humans. What matters is their relative position in vector space. Text that carries a similar meaning tends to produce vectors that are located closer together. Text that differs in meaning will be positioned farther apart. This spatial relationship is what enables semantic similarity search.

Snowflake supports a native VECTOR data type that allows you to store embeddings directly in tables. The dimension size must match the output size of your embedding model.

A simplified table definition looks like this:

CREATE TABLE documents (

id STRING,

content STRING,

embedding VECTOR(FLOAT, 768)

);

Snowflake does not automatically convert text into embeddings. You must generate them either:

• Using Snowflake Cortex embedding functions such as AI_EMBED

• Or by generating embeddings externally and loading them into Snowflake

Once embeddings are stored, Snowflake provides similarity functions such as COSINE_SIMILARITY and vector distance functions to compare vectors. At query time, the user’s input is converted into a query embedding, and similarity scores are computed between that query vector and stored document vectors.

A typical semantic retrieval query pattern looks like this:

SELECT id, content,

COSINE_SIMILARITY(embedding, :query_vector) AS score

FROM documents

ORDER BY score DESC

LIMIT 10;This shifts retrieval from string comparison to mathematical distance evaluation. Instead of matching tokens, the database evaluates geometric closeness in vector space.

The next important concern for data engineers is scale. Computing similarity across millions of vectors introduces performance considerations. That brings us to indexing strategy, clustering, and architectural patterns for large workloads.

Similarity Search at Scale: Performance and Architectural Considerations

Vector similarity looks simple in a demo. You compute cosine similarity, sort by score, and return the top results. The challenge appears when the table holding embeddings grows large.

In Snowflake, similarity functions such as COSINE_SIMILARITY are evaluated at query time. If no filters are applied, Snowflake scans the candidate rows and computes similarity scores against the query vector. For smaller datasets, this works well. For larger datasets, you need to design intentionally.

The first principle is the reduction of the candidate set.

Always apply structured filters before similarity scoring. Filter by tenant, document type, language, business unit, or any relevant metadata. This converts a full scan into a scoped evaluation. Hybrid search, combining metadata filtering with semantic similarity, is the practical production pattern.

The second principle is workload clarity.

Ask yourself what this system is serving. Internal analytics tools can tolerate higher latency. Customer-facing applications may require tighter response times. Snowflake can scale compute, but scaling compute increases cost. Benchmarks under realistic load matter more than theoretical capability.

The third principle is architectural honesty.

Snowflake performs similarity calculations, but it is not a purpose-built approximate nearest neighbor engine. For very high volume, ultra-low latency search across massive embedding collections, specialized vector databases may offer indexing advantages. For many enterprise use cases, though, keeping embeddings and retrieval logic inside Snowflake simplifies governance, security, and operational complexity.

The goal is not to force everything into one platform. The goal is to choose the right design based on workload characteristics.

Now that performance considerations are clear, let’s move into the practical side.

End-to-End Implementation Workflow in Snowflake

Designing semantic search in Snowflake follows a clear sequence. Once you understand the flow, it becomes repeatable.

Step 1: Generate Embeddings

You need an embedding model. In Snowflake, you can use Cortex functions such as AI_EMBED to generate embeddings directly within SQL. Alternatively, embeddings can be generated externally using models from OpenAI or other providers, then ingested into Snowflake.

An example using Cortex might look like this:

SELECT

id,

content,

AI_EMBED('snowflake-arctic-embed-m', content) AS embedding

FROM raw_documents;The model name and output dimension must align with your table definition. If the model produces 768-dimensional vectors, your table column must match that size.

If you generate embeddings outside Snowflake, ensure the numeric precision and ordering are preserved during ingestion.

Step 2: Store Embeddings

Create a table with a VECTOR column sized to the embedding model:

CREATE TABLE documents (

id STRING,

content STRING,

embedding VECTOR(FLOAT, 768)

);Embeddings are inserted just like any other column value. At this point, your semantic data layer exists inside Snowflake.

Step 3: Generate Query Embedding

When a user submits a search query, you convert that query into a vector using the same embedding model used for documents. Consistency here is critical. Mixing models breaks similarity behavior.

SELECT AI_EMBED('snowflake-arctic-embed-m', 'customer churn signals');The result becomes your query vector.

Step 4: Perform Similarity Search

Now compute similarity and rank results:

SELECT id, content,

COSINE_SIMILARITY(embedding, :query_vector) AS score

FROM documents

ORDER BY score DESC

LIMIT 5;This returns the most semantically similar records.

Step 5: Integrate with Downstream Systems

For retrieval augmented generation workflows, the top results are passed into an LLM as contextual input. For internal search tools, the results are displayed directly to users. For analytics use cases, similarity scores may feed ranking models or recommendation systems.

At this stage, semantic search is fully operational inside Snowflake.

Key Takeaways and Pro Tips for Data Engineers

• Snowflake supports native vector storage through the VECTOR data type, allowing embeddings to be stored and queried directly within the platform instead of moving data to external systems.

• Semantic search evaluates similarity in vector space rather than matching keywords, which makes it well-suited for AI-driven search, contextual knowledge retrieval, and retrieval-augmented generation workflows.

• Use a single embedding model consistently for both document and query vectors to preserve semantic alignment and ensure reliable similarity scoring.

• Combine structured metadata filtering with vector similarity calculations to narrow the candidate set and improve both relevance and query efficiency.

• Define a deliberate chunking strategy, since embedding logically segmented content typically produces better retrieval accuracy than embedding large documents as single vectors.

• Benchmark similarity queries using realistic data volumes and concurrency patterns and monitor warehouse consumption to balance performance with cost.

• Treat embeddings as first-class data assets by storing contextual metadata, managing model versions carefully, and evaluating retrieval quality as the system evolves.

Conclusion

Semantic search inside Snowflake represents a practical evolution in how data platforms support AI-driven systems. By introducing native vector storage and similarity functions, Snowflake allows data engineers to extend traditional analytical workflows into meaning-based retrieval without leaving the governed data environment.

If you are exploring semantic search inside Snowflake and want to move beyond proof of concept into a production-ready architecture, the right design decisions matter early. Stridely works closely with data teams to design, implement, and optimize Snowflake-based AI and semantic retrieval systems that are technically sound and built for real workloads.

Explore Stridely’s Snowflake capabilities or connect with our team to see how semantic search can fit into your data architecture. Contact us for a demo today.